US economics, inflation, and the Fed

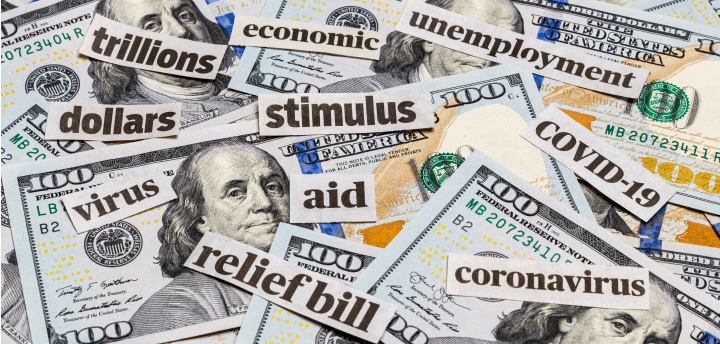

The US economy declined at a 1.5% annual rate in the first quarter and, recently, the Atlanta Fed’s “GDP Now” model projected zero growth in Q2. The consensus still points to a positive second quarter, but if you take the Atlanta GDP Now model at face value, it superficially appears that the odds of having two consecutive quarters of negative growth are close to 50%. That’s important because two consecutive quarters of negative growth is a textbook definition of a recession.

At some point, a recession will happen in the US, but we are not there yet. The stats point to a very strong economy: in the first five months of the year, manufacturing production is up at a 6.6% annual rate, nonfarm payrolls are up at an average monthly pace of 488,000, and the unemployment rate has dropped to 3.6% from 3.9%. Meanwhile, in April, both “real” (inflation-adjusted) consumer spending and real personal income (excluding transfers) were at record highs.

“If this is a recession, we could use more recessions,” says Brian Wesbury, Chief Economist of First Trust. “Again, we expect a recession, with a lag, after monetary policy gets tight. And tight it must get to wrestle inflation back down toward the Federal Reserve’s 2.0% target. But that means a recession starting in late 2023 or 2024, not now. Even more unlikely is the notion that the US is on the cutting edge of a recession like the one in 2008-09. Bank capital is well above regulatory requirements, and we don’t have a mark-to-market accounting rule that will generate a “fire sale” in bank assets. Nor are we about to have a government lockdown of the private sector, like in 2020.”

We agree with the assessment above and closely follow the Federal Reserve aggressively tightening monetary policy to fight inflation. This more-restrictive monetary policy stance included a three-quarter-point increase to the benchmark short-term interest rate at the June Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, the largest hike in 28 years. The central bank increased its inflation forecasts for this year and next. This prompted the FOMC to raise the federal funds rate targets for 2022 and 2023 from 1.9% and 2.8% to 3.4% and 3.9%, respectively. The strong 12-month advances in May consumer and producer prices likely played a part in this reassessment according to Value Line.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said the central bank needs to stay aggressive on the rate front to slow demand and hopefully put downward pressure on prices. The Fed also reiterated its stance on reducing the central bank’s bloated balance sheet. This month, it began selling $30 billion of Treasury holdings and $17.5 billion of mortgage-backed securities. After three months, the Fed plans to double the monthly bond selling to $95 billion if the economy cooperates. This decreases the amount of liquidity or money supply in the economy, to lower demand and ultimately rein in inflation.

Global economy

While having flagged downside risk to the second half of 2022 global growth outlook for some time, thus far JP Morgan has made only modest revisions to its forecast for a return to above-trend global growth. Much of this anticipated acceleration comes from a sharp reopening rebound in China that has already begun. But the bank’s forecast elsewhere — to a solidly above-potential 2.2% annual growth in the second half of 2022 — is under greater threat.

Indeed, recent developments have shifted the focus of the debate in the US and Western Europe to the risk of recession. As has been the case preceding prior downturns, both regions have been hit by large adverse supply shocks that have pushed price indexes above 8% on an annual basis in the first half of the year. Thus far, households have cushioned the blow to their purchasing power by drawing down their savings. But consumer confidence is now sliding, with Euro area and UK June readings both approaching 40-year lows. Other regional June readings should also show that inflation pressure remains intense at midyear.

Easing supply pressures are apparent in notable declines in industrial metal and agricultural commodity prices in recent weeks as well as shortening delivery times in available June business surveys. However, this relief is of limited comfort as its main source is softening demand. Global consumer goods spending contracted in the three months through May (even if a China dive is excluded). Nevertheless, JP Morgan forecasts the US economy to grow by 2.4% this year and the global GDP — by 3%.

A bear market transition

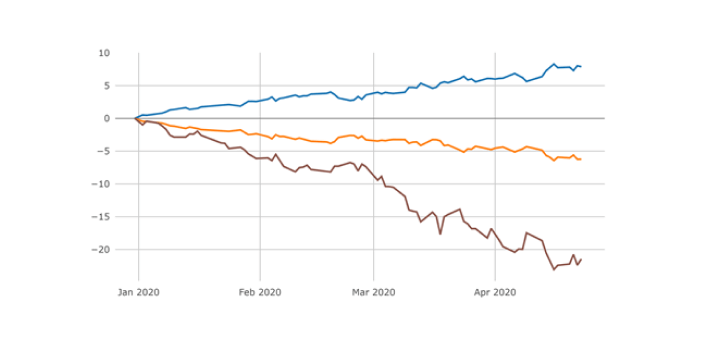

According to Goldman Sachs (GS), most major equity markets have now moved into the official bear market territory. The damage beneath the surface has reflected the shift higher in the cost of capital (with long-duration stocks being hit most) and recession risks (with many cyclical underperforming defensives).

There are now two critical issues for investors. First, how much further can equities adjust before the trough, and second, what kind of characteristics will the new cycle exhibit? GS looked at bear markets back to the 1900s and divided them into three types: structural, cyclical, and event-driven — they looked at the average performance and duration for each bear market. GS views this as a ‘cyclical’ bear market with stronger private sector balance sheets and negative real interest rates cushioning against many of the systemic risks associated with the longer and deeper ‘structural’ bear markets.

On average cyclical bear markets drop around 30% from peak to trough and the last two years — in terms of performance we are getting close to this kind of sell-off but the duration is so far shorter. GS finds the trough in a cyclical bear market typically comes around 6–9 months before the trough in earnings (EPS), and 1-2 quarters before the economic nadir post the peak in inflation. The turning point is often around the period when rate expectations start to moderate.

From a valuation perspective, while there has been a considerable de-rating, and some markets are trading with below-average valuations, pricing is more consistent with a mild recession than an average or deep recession, leaving them exposed to a further deterioration in expectations. In addition, virtually every recession in the last 30 years has been a function of a demand shock but this is a supply shock. This means that monetary policy is less potent, requiring more fiscal intervention, and this is especially worrisome at a time when debt/GDP ratios are high.

In terms of the new cycle drivers, GS argues that the Post Modern Cycle will be materially different from the past two cycles. Inflation risks, scarcer resources, and more regionalization are likely to result in more CapEx and lower margins and returns for investors. GS expects lower aggregate returns and a ‘fatter & flatter’ market profile with greater alpha opportunities.

The information and opinions included in this document are for background purposes only, are not intended to be full or complete, and should not be viewed as an indication of future results. The information sources used in this letter are: WSJ.com, Jeremy Siegel, Ph.D. (Jeremysiegel.com), Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, Empirical Research Partners, Value Line, BlackRock, Ned Davis Research, First Trust, Citi research, HSBC, and Nuveen.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURE

Past performance may not be indicative of future results.

Different types of investments and investment strategies involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that their future performance will be profitable, equal to any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s), be suitable for your portfolio or individual situation, or prove successful.

The statements made in this newsletter are, to the best of our ability and knowledge, accurate as of the date they were originally made. But due to various factors, including changing market conditions and/or applicable laws, the content may in the future no longer be reflective of current opinions or positions.

Any forward-looking statements, information, and opinions including descriptions of anticipated market changes and expectations of future activity contained in this newsletter are based upon reasonable estimates and assumptions. However, they are inherently uncertain, and actual events or results may differ materially from those reflected in the newsletter.

Nothing in this newsletter serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice. Please remember to contact Signet Financial Management, LLC, if there are any changes in your personal or financial situation or investment objectives for the purpose of reviewing our previous recommendations and/or services. No portion of the newsletter content should be construed as legal, tax, or accounting advice.

A copy of Signet Financial Management, LLC’s current written disclosure statements discussing our advisory services, fees, investment advisory personnel, and operations are available upon request.